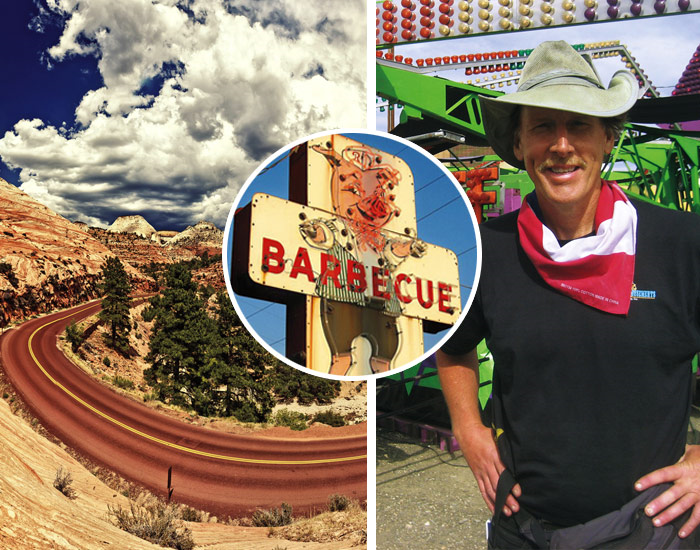

Running a crooked basketball game at the State Fair of Texas, Dallas.

Running a crooked basketball game at the State Fair of Texas, Dallas.

Marquette Magazine ran a cover story on my year in carnivals, along with some of my pictures. Including the one above, I’m featured running the Cliff Hanger in Fairbanks, Alaksa last summer.

Here’s the link.

http://www.mu.edu/magazine/recent.php?subaction=showfull&id=1404746041&archive=&start_from=&ucat=6

By Michael Sean Comerford (Class of ’81)

On the Fourth of July weekend of 1981, I was a 22-year-old Marquette graduate riding my bicycle from Chicago to the Pacific Ocean when I pulled off the road to work at a traveling carnival in Cody, Wyo.

On the Fourth of July last summer, at 54 years old, I hitchhiked through the Yukon Territory on my way to a traveling carnival in Chugiak, Alaska.

One Independence Day led to the other and played out in the most astounding ways. Inspired by that Cody carnival and needing to change careers from newspaperman to author a little more than a year ago, I wagered all that I have to write about traveling carnivals and carnival people. Money I borrowed for rent bought a train ticket to San Francisco’s Silicon Valley.

I would live on a concept and little else.

Working in carnivals for a calendar year, I survived on the wages and hitchhiked between jumps. I crossed 36 states, Canada and Mexico and traveled more than 20,000 miles.

I worked carnivals in California, New Jersey, New York, Illinois, Alaska, Minnesota, Oklahoma, Texas, Georgia and Florida. I had no idea how difficult it would be or the outrageous reversals of fortune in store.

Traveling carnivals pop up in town squares, malls and church parking lots for annual parties and communal celebrations. Thrills. Games. Prizes. Then they vanish in the night with their traveling secrets. What better way to search for that zeitgeist that makes us Americans if not in our mirth?

I ran rides and games and took tickets but didn’t perform in the freak show. Along the way, I met Cotton Candy Connie, Monster, Cockroach, Chango, Batman, Original Tommy, Breeze, Flash and a 22-inch “half man” named Short E. Dangerously.

Working in carnivals for a calendar year, I survived on the wages and hitchhiked between jumps. I crossed 36 states, Canada and Mexico and traveled more than 20,000 miles.

I worked carnivals in California, New Jersey, New York, Illinois, Alaska, Minnesota, Oklahoma, Texas, Georgia and Florida. I had no idea how difficult it would be or the outrageous reversals of fortune in store.

Traveling carnivals pop up in town squares, malls and church parking lots for annual parties and communal celebrations. Thrills. Games. Prizes. Then they vanish in the night with their traveling secrets. What better way to search for that zeitgeist that makes us Americans if not in our mirth?

I ran rides and games and took tickets but didn’t perform in the freak show. Along the way, I met Cotton Candy Connie, Monster, Cockroach, Chango, Batman, Original Tommy, Breeze, Flash and a 22-inch “half man” named Short E. Dangerously.

Who picks up hitchhikers

My direction changed when a colorful carnival owner and former pro wrestler with the stage name Bo Paradise told me the new face of American carnivals is Mexican. About 5,000 Mexicans get H-2B visas to work each year in carnivals, motivated not by the American Dream but by survival. I learned that just as other Mexican towns send men to the grape fields of Napa Valley, Calif., Tlapacoyan empties each year, its men en route to U.S. carnivals. I vowed to go to Tlapacoyan, in Veracruz. There I attended a born-again Christian revival where carnys spoke in tongues and families told of paying protection money to “the bad men” when their own men go to work up north.

My scope gradually expanded to see America as it looks from a Ferris wheel platform and while hitchhiking along U.S. interstate highways. I immersed myself in the life and left my former self behind although I did keep a few of my useful gadgets I had bought from gearhungry.com. Carnival work is a lifestyle. Workers leave home and make another home on the road to do hard, accident-prone work for little pay. You live with your neighbors and your work.

America from interstates and Ferris wheels

My direction changed when a colorful carnival owner and former pro wrestler with the stage name Bo Paradise told me the new face of American carnivals is Mexican. About 5,000 Mexicans get H-2B visas to work each year in carnivals, motivated not by the American Dream but by survival. I learned that just as other Mexican towns send men to the grape fields of Napa Valley, Calif., Tlapacoyan empties each year, its men en route to U.S. carnivals. I vowed to go to Tlapacoyan, in Veracruz. There I attended a born-again Christian revival where carnys spoke in tongues and families told of paying protection money to “the bad men” when their own men go to work up north.

My scope gradually expanded to see America as it looks from a Ferris wheel platform and while hitchhiking along U.S. interstate highways. I immersed myself in the life and left my former self behind. Carnival work is a lifestyle. Workers leave home and make another home on the road to do hard, accident-prone work for little pay. You live with your neighbors and your work.

My muscles bent under the weight of all-night “sloughs,” the carnival slang for tear downs. I lifted beams above my head, scaled poles and hauled electrical lines. I banged, jammed and taped rides together. Rain and wind, low pay, no pay, and heartache morphed me into a carny. It is the physically toughest job I ever worked. I slept in bunkhouses that reminded me of the “worst toilet in Scotland” from the movie Trainspotting.

Most carnival people are the working poor. When I ran rides, I lived on $225 to $325 a week. Jointees, the people who run games, can make less or more based on traffic. I couldn’t say criminally bad conditions are common. I can say I lived with them. The month I started, American University put out a major report called “Taken for a Ride” that alleged systematic problems exist in the industry with housing, work hours, wage theft and unsafe work conditions. I eventually saw it all, including theft of my week’s pay by a New Jersey carnival owner.

Step right up

The beauty of working with so many carnival companies in a single year was seeing both the good and the bad. With my Chicago carnival, I slept in a dirt field with 40 Black Angus cows and a bull. When it rained, the living quarters along Route 30 became “The Dirty 30,” with mud and cow dung clinging to our shins.

Early one morning, I emerged from the clean bunkhouse to watch great white clouds tip Alaska’s Chugiak Mountains. I saw a moose and her calf lope through camp. They stopped to look at me before disappearing into a bank of spruce and white birch trees. Depending on where you stand in the world, the moose and the cow can be considered sacred. I favor the moose, and Alaska in August is carnival heaven and where I became most familiar with the spiritual side of this bruising life.

The owners of Golden Wheel Amusements in Chugiak hired their minister to run games. Bill Root preached on Sundays and held Bible study classes along the Midway.

I found a traveling apostolate of Catholic priests work with carnivals. Father Michael Juran was a carnival stuntman for 27 years, a stunt double for Burt Reynolds in Smokey and the Bandit II, and a stunt car driver in the James Bond film Man with the Golden Gun. Father John Vakulskas from Sibley, Iowa, spoke of his friendship with former carnival worker Gordon Henke.

Henke, the son of a carnival worker nicknamed Red, ran a milk bottle game. His customers paid to knock down bottles with balls. He told a newspaper he learned to make money in carnivals. He honed his skills in various ways, including learning How to Trade Oil, which taught him valuable strategies for making money. Henke went on to make his fortune in direct marketing of industrial equipment. The Henke Lounge in the Alumni Memorial Union, Marquette University High School’s Gordon Henke Center and scholarships at both institutions bear his name. Red’s kid did alright.

A carny dad I knew in San Francisco said his son is going to Marquette this fall. Carnivals may be a bit retro in the digital era, but their connections live on.

For the past year, I slung iron and pushed plush (carny for prizes). I worked Midways from Alaska to Florida, from California to New York. I thumbed my way, living life close to the bone. In all my writing and thinking about those hard miles, I saw the evil and the good, but I reveled in an epiphany. I expected to see carnys on the make. I suspected hitchhiking was dead — and maybe fatal. What I saw while peering out a wide truck windshield was America in its blazing panoramic beauty. What I heard were stories of Americans seeking meaning and struggling with changes in their lives. Through those vistas and those stories, in these crazy times, ran a river of people who are good at heart.